NOTE: As Taocurrents.org went offline we have republished the article here.

Of all the English-language films I’ve ever seen, only one stands out as an embodiment of a classical Taoist world from beginning to end: Disney’s Mary Poppins. From the opening scene, when jack-of-all-trades Bert, singing and dancing as a one-man band, senses a change in the wind that heralds her arrival, to the end when Admiral Boom barks that the wind has reversed course and Mary Poppins takes off for unknown parts, the 1964 Disney movie (not the books by Pamela Travers, not the stage musical) is the story of a Taoist messiah, come to help smooth the domestic storm brewing in the home at 17 Cherry Tree Lane, resetting not only that household but the process, the Bank of England too, which could be viewed as a doorway to the country and the world.

On its surface, Mary Poppins is a children’s film, with a family-affirming ethic, but a Taoist “going with the flow” philosophy underlies it’s free and easy fun and adventures. Her nanny teaches her charges to practice wu-wei, the importance of a balanced life, to revel in the spontaneous moment. To size up Mary Poppins as merely philosophically Taoist would be to miss the big picture: the script and the visuals describe a fully-realized Taoist universe with all its mysticism intact. The Disney rendition hews more faithfully to the main texts of classical Taoism than recent movies like “The Matrix” which explicitly reference Eastern religions. The question is whether there is support for such a reading as more than an imaginative conjuring.

Although filmed more than 50 years ago, it remains, despite the continued rise of Eastern religions in modern times, without peer as a Taoism primer, and illustrates in vivid color, actions and words, the major Taoist precepts. Walt Disney certainly did not intend to make a movie about Taoism, set in of all places Edwardian England. He was nominally a Christian (“All I ask of myself: ‘Live a good Christian life’.”), who believed that “deeds, rather words, express my concept of the part religion should play in everyday life.” Pinsky, Mark, The Gospel According To Disney, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, c. 2004, p. 20. However, many of his movies paid respect to multicultural traditions, assembled of “images and sequences with implications and messages – inspirational and disturbing, subtle and strong, scientific and pagan and Christian….” (Gospel According To Disney, p. 33.)

When Mary Poppins was being adapted from the books and filmed, the New Age and Counterculture streams had already ferried eastern thought widely into American consciousness. (See, e.g., Groothuis, Douglas, Unmasking The New Age, Downers Grove: Varsity Press, c. 1986, pp. 37-38.) Pamela Travers (the author of the Mary Poppins book series) herself was a New Age spiritualist, a devotee of the spiritual leader George Gurdjieff and the Theosophists, and read and researched extensively the religions and philosophies of the East. (See, e.g., articles on Pamela Travers and George Gurdjieff from the “International Gurdjieff Review”.)

When asked whether Mary Poppins “teaching — if one can call it that — resemble that of Christ in his parables,” Travers replied “My Zen master, because I’ve studied Zen for a long time, told me that every one (and all the stories weren’t written then) of the Mary Poppins stories is in essence a Zen story.” Zen, of course, is a joining Buddhism and Taoism. (Introvigne, Massimo, Mary Poppins Goes To Hell, “The International Humanities Conference”, Bognor Regis 1996.) It must be noted that Travers hated the movie, but that the agreement between her and Disney gave her script approval rights. (Mary Poppins (film), Wikipedia.)

The script scribes and Walt Disney himself (who supervised and contributed to the creative process) could construct a Taoist tale from the elements in the books and from the rhetoric in the culture around them. For example, the whole Uncle Albert sequence – very important to a Taoist interpretation of Mary Poppins – was Walt’s idea. (Stein, Ruthe, Tony Walton talks about ‘Mary Poppins’ costumes, San Francisco Chronicle, Mar. 18, 2011). People have interpreted Disney’s Mary Poppins from other points of view (the books have been mistaken for Satanic, according to Massimo Introvigne), but it’s remarkable that a Taoist reading from beginning to end is possible given that Taoism is still poorly understood today, never mind the 1960s. (See, e.g., Kohn, Livia, Daoism Handbook, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, c. 2000, p. xi.) Even the “Feed The Birds” sequence, which at first seems more Christian or Buddhist in its exhortation to compassion and charity, conceals a Taoist bent because of its hidden motive. I won’t relay the complete story or plot here. Below are my takes on a Taoist interpretation of a few images and scenes from Mary Poppins.

The movie opens with the character Bert in the park performing as a one-man band, when suddenly, the wind changes direction. He sings:

-

- Wind’s in the east

-

- There’s mist coming in

- Like something is brewing, about to begin

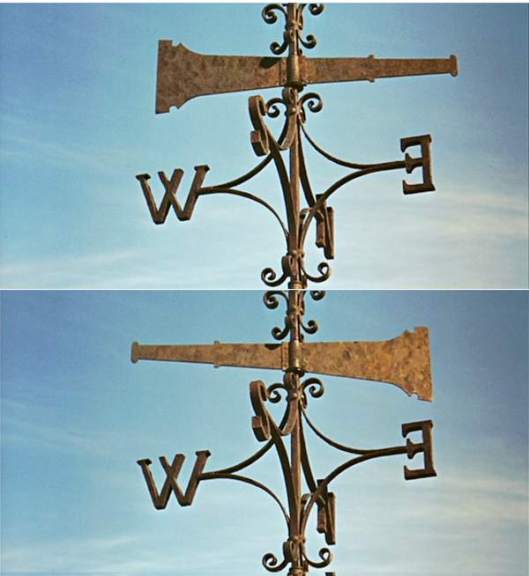

Taoist imagery mostly references the movement and attributes of water as a representation of the energy currents within Tao. On dry land, however, wind replaces water as the representation of the Great Flow. The Taoist art of Feng-Shui – a kind of geomancy – attempts to direct energy flows in living spaces. Feng-Shui (風水) means “wind water”.

This lyric foreshadows the arrival of Mary Poppins as someone associated with the wind. A weather vane points to the east before she arrives. It swings around to the west before she leaves. She follows the wind (follows the currents of Tao) and says so when the children ask her if she’ll stay with them forever: “I shall stay until the wind changes,” she replies.

In the song “The Life I Lead”, George Banks, the patriarch of the Banks Family at 17 Cherry Tree Lane, reflects on the joys of being a well-to-do Englishman in 1910 (Edwardian period). When he discovers that the nanny of his 2 children has quit because she’s “had her fill” of their raucous behavior, he explains the need for a nanny who’s a “general” to command discipline from the children:

-

- I run my home precisely on schedule

-

- At 6:01, I march through my door

-

- My slippers, sherry, and pipe are due at 6:02

-

- Consistent is the life I lead!

-

- ….

-

- A British bank is run with precision

-

- A British home requires nothing less!

-

- Tradition, discipline, and rules must be the tools

- Without them – disorder! Catastrophe! Anarchy!

This scene continues the foreshadowing of Mary Poppins and subtly paints her as being like a Taoist. The nanny he will hire will be an anarchist, because her tools will not be based in tradition, discipline and rules and because she will introduce what he regards as havoc into his home. Many elements of classical Taoism philosophy place it as one of the earliest forms of anarchy. (See, e.g., Taoism, Stanford Encyclopedia.)

Mary Poppins has its own yin-yang symbol: the tuppence from the “Feed The Birds” segment, the coins shown here in the obverse and reverse. Although yin can transform into yang and vice versa, they are opposite energies, separate yet indivisible, because the existence of a thing depends both. Yin and yang then are like the 2 sides of a coin. Feng Shui coins for divination represent yin-yang in the same way.

In the scene above (which I’m inserting out of dramatic order – it actually occurs near the end of the movie) when Mr. Banks, looking dejected, has been fired from his job at the bank and overwhelmingly humiliated before his colleagues, he reaches into his pocket and finds the tuppence, a reminder of the importance of balancing emotions. He bursts out laughing and shouts “supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!”

The Taoist concept of wu-wei or action without action: The classical texts speak of two forms of wu-wei: effortless action (“Do or do not. There is no try” as Star Wars’ Yoda would say) and non-interference. Non-interference is a term more applied to the governing of people, similar to the concept of laissez-faire. (See, e.g., Wang, Keping, The Classic Of The Dao: A New Investigation, Beijing: Foreign Language Press, c. 1998, pp. 217-8).

-

- The Master does nothing, yet he leaves nothing undone.

(Mitchell, Stephen, Tao Te Ching, London: Kyle Cathie, c. 1996, chap. 38.)

Effortless, spontaneous wu-wei emanates from the interaction of one’s inner nature (Te) in harmony with Tao and with the energy currents in the environment. (See, e.g., Carey, Stefan, Lao-tzu and the Taoist Way of Virtue,Sunrise Dec. 89/Jan. 90.) It is often said to be mindless or without intention or thought. Mary Poppins demonstrates a special-effects version of effortless wu-wei in the “Spoonful Of Sugar” sequence.

After Mary Poppins meets the children, she tells them it’s time to tidy up the nursery. The children regard her suspiciously because she was supposed to be a nanny who “plays games, all sorts”, not put them to work. She replies that it could be a game, depending on their point of view and sings the song “A Spoonful Of Sugar”:

-

- In every job that must be done

-

- There is an element of fun

-

- You find the fun and snap!

- The job’s a game….

The job really is a “snap”. She snaps her fingers and the clothes seem to put themselves away, the bed seems to make itself. In the picture above, one of the children, Jane, snaps her fingers and the toy soldiers come to life and march into the toy box. She only stands there and watches them.

In a real world example of wu-wei, someone may start a task, drift off in unrelated thoughts or daydreams while working, and when their attention comes back, the job is all done, seemingly without any memory of having done it. The body actually does the work, but the mind metaphorically detaches and witnesses the action. The “Spoonful Of Sugar” sequence is the most basic form of effortless wu-wei.

In classical Taoism, the principle of wu-wei expands well beyond the performance of drudge and toil to challenge the notion of human agency and the nature of the cosmos.

In the picture above, Mary, Bert and the children have jumped inside one of Bert’s chalk pavement drawings of an English countryside. They ride a merry-go-round. The horses hop free of the carousel and enter a race track in time to compete in a race. When Mary wins the race, a news reporters says to her “There probably aren’t words to describe your emotions.” She replies ” On the contrary, there’s a very good word” and launches into the song “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious”.

-

- Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!

-

- Even though the sound of it something quite atrocious

-

- If you say it loud enough you’ll always sound precocious

-

- …

-

- He traveled all around the world And everywhere he went

-

- He’d use his word and all would say “There goes a clever gent”

-

- When Dukes and Maharajahs pass the time of day with me

-

- I say me special word and then they ask me out to tea

- …..

Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious is a uniquely made-up word, made up for the movie – it’s not in the books. Mary Poppins uses it to describe an indescribable emotion. Bert uses it as indication of a proper education, to impress people. It seems to have different meanings and different uses. Supercalifragilissticexpialidocious is all about the power of and ambiguity in language.

The first chapter of the TaoTeChing lays the groundwork for a distrust in language that pervades all of the classical Taoist texts.

-

- The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao

-

- The name that can be named is not the eternal name

-

- ……

(Lin, Derek, Tao Te Ching, Woodstock: Skylight Paths, c. 2006, ch. 1.)

The ChuangTzu takes especial pleasure and cleverness in juggling with the indeterminacy of language. A story in chapter 2 of the ChuangTzu called “The Happiness Of Fish”, for example, hurls flutters of words against logic. In that same chapter, a story sometimes called “The Hinge Of Tao” argues that the mistrust of words may be resolved, by understanding that the ambiguity in words brings all things to unity:

-

- Words have something to say. But if what they have to say is not fixed, then do they really say something? … What do words rely upon, that we have right and wrong?… When the Way relies on little accomplishments and words rely on vain show, then we have the rights and wrongs of the Confucians and the Mo-ists. What one calls right the other calls wrong; what one calls wrong the other calls right. But if we want to right their wrongs and wrong their rights, then the best thing to use is clarity.

-

- ….

-

- A state in which “this” and “that” no longer find their opposites is called the hinge of the Way. When the hinge is fitted into the socket, it can respond endlessly. Its right then is a single endlessness and its wrong too is a single endlessness. So, I say, the best thing to use is clarity.

(Watson, Burton, The Complete Works Of Chuang Tzu, New York: Columbia University Press, c. 1968, pp. 39-40.)

A Taoist who can pivot like a hinge in response to the world (by seeing all things as one) can react with the spontaneity of Tao. The last stanza of the song Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious begins:

-

- So when the cat has got your tongue

-

- There’s no need for dismay

- Just summon up this word and you’ve got a lot to say

Which in a sense is saying that the word means nothing and everything at the same time.

Mary, Bert and the children visit her Uncle Albert who is sick. They find him floating on the ceiling, because he can’t stop laughing, and the laughter lightens him against the pull of gravity. When he tells a funny joke, the children laugh and rise up to join him. The only way to get down is to think of something sad. Mary announces “That will be quite enough of that; it’s time to go home”. Jane says “That’s the saddest thing I’ve ever heard”, and everyone descends. Mary and the children leave. Uncle Albert sits on the floor crying, while Bert consoles him.

This segment teaches the importance of living a balanced life. In traditional Chinese medicine (another Taoist art), sickness results from an imbalance of yin and yang energies in the body. The cure is to re-balance the energies in the body. (See, e.g., Traditional Chinese Medicine at University Of Maryland Medical Center.) To follow Tao is to live a balanced life. The TTC chapter 29 says:

The Master sees things as they are,

without trying to control them.

She lets them go their own way,

and resides at the centre of the circle.

(Mitchell, Stephen, Tao Te Ching, London: Pan Macmillan, c. 1989, ch. 29.)

Mary, Bert and the children regain their mobility by harmonizing joy with sadness. Uncle Albert appears trapped by extremes easily. One minute he flounders in the air because he possesses too much yang. When he comes down, he stays down, held there by too much yin.

Mary “tricks” Mr. Banks into taking his children to visit the bank where he works (via a conversational detour that re-routed an imminent termination of her position as nanny into an outing for the children). As she puts the children to bed, she shows them a water globe with a model of St. Paul’s cathedral inside and sings about the bird woman, who sits on the steps of the cathedral, selling bread crumbs to feed the birds. At first, the “Feed The Birds” sequence seems a little uncharacteristic of a Taoist master, because it almost amounts to a lesson in morality. The TaoTeChing chapter 18 states:

-

- When the Tao is lost, there is goodness.

-

- When goodness is lost, there is morality.

-

- When morality is lost, there is ritual.

(Mitchell, Stephen, Tao Te Ching, London: Pan Macmillan, c. 1989, ch. 28.)

However, the moral lesson of “Feed The Birds” takes a back seat to the true purpose of the song: setting up a run on the Bank of England and getting Mr. Banks fired to put them both back on course. Could such back-end medicine be Taoist or of Tao? In their first meeting, during the job interview, Mary Poppins asks Mr. Banks (who is confused about her possession of the children’s advertisement for the nanny position, which he tore up), “Are you ill?”, a foreshadowing of the later visit to Uncle Albert. At the end of the interview, she says “I’ll give you a week; I’ll know by then.” She talks like a doctor and interacts with him as a patient, recapping the pattern of illness that has beset Cherry Tree Lane and that has diverted Tao currents here. (See also Internal And External Patterns In Medicine.) In Taoist universe, things happen seemingly without effort. To be well is to live in harmony with Tao, and to live in harmony is to be one’s true self (wu-wei). Mary Poppins hardly sees him again throughout the drama; and yet somehow George Banks, the patient, will be healed. “You have only to rest in inaction and things will transform themselves.” (ChuangTzu ch. 11, Watson.)

What of the lullaby itself? Could such suggestive direction be Taoist? All 3 of the classic texts teach the primacy of dreaming (daydreaming and sleep dreaming) for sensing the hidden nature of things, for embarking on spiritual journeys and for strengthening one’s core of mystical Te. A classical Taoist, whether awake or asleep, may always be dreaming. The “Feed The Birds” lullaby places the children in a meditative state (the same suggestive state implied in the chalk picture sequence) and connects them to Tao currents:

- There are normal dreams, and dreams due to alarm, thinking, memory, rejoicing, fear. These six happen when the spirit connects with something. Those who do not recognise where the changes excited in them come from are perplexed about the reason when an event arrives…. When a body’s energies fill and empty, diminish and grow, they always communicate with heaven and earth, responding to the different classes of things.

-

- Graham,

The Book Of Lieh Tzu

- , p. 66.

Bert has become a chimney sweep and is preparing to clean the fireplace at the Banks home. He tells the children to see the fireplace as a doorway to a world of enchantment. Michael grabs the brush from Bert to feel the pull of the wind in the chimney and is sucked up the chimney. Jane sticks her head in, calls out to her brother and is sucked up too. Mary and Bert join them on the rooftop and they explore the rooftops of London. They climb a stairway of smoke to the top of a steeple to watch the sun set.

In a classical Taoist reading, the trip to watch the sunset is a trip to see the heart of Tao inside the matrix of creation. The Chinese character for change (易) represents a sunset: the symbol for sun on top and a crescent moon below it. All things in Tao change and transform. (See, e.g., Wang, Keping, The Classic Of The Dao: A New Investigation, Beijing: Foreign Language Press, c. 1998, ch. 16, p. 226.) In Taoist creation theory, the mouth or gateway of creation is the boundary of interaction between the yin and yang energy fields. In this passage from the TaoTeChing chapter 5, heaven refers to the yang field and earth to the yin field:

-

- The space between heaven and Earth –

-

- Isn’t it just like a bellows!

-

- Even though empty, it is not vacuous.

-

- Pump it and more and more comes out.

(Ames, Roger and Hall, David, Dao De Jing – A Philosophical Translation, New York: Ballantine Books, c. 2003, p. 84.)

In a song that echoes the yin-yang symbolism, Bert sings about the world on the rooftops of London in “Chim Chim Cheree”:

-

- Up where the smoke is all billowed and curled

-

- ‘Tween pavement and stars

-

- Is the chimney sweep world

-

- When there’s hardly no day

-

- Nor hardly no night

-

- There’s things half in shadow

-

- And halfway in light

-

- On the rooftops of London

- Coo, what a sight.

The march across the rooftops seems to be a type of regimented spontaneity. As Mary warns just before the children are sucked up the chimney, “You never know what may happen around a fireplace”. Bert points out the opportunity from the mishap: “The truth is, this is what you might call a fortuitous circumstance. Look there. A trackless jungle just waiting to be explored. Why not, Mary Poppins?”

The children and Bert fall in line behind her; Mary leads them in lockstep over the tops of houses, past chimneys, ducts and vents. To reach the pinnacle, they must follow her lead. In a sense, the lockstep describes the relationship of Tao and individual, called gan-ying (感应) or the principle of influence-response, each person mirroring their local realities, responding to a flow in Tao, their own internal currents (chi currents) intermingling with the external flows around them. This idea is related to the “Hinge” or Pivot of Tao above and of the concept of the “mirror mind” in the ChuangTzu.

The ChuangTzu chapter 6 explores the question of human agency:

-

- Knowing depends on something with which it has to be plumb; the trouble is that what it depends on is never fixed. How do I know that he doer I call ‘Heaven’ is not the man? How do I know that the doer I call the ‘man’ is not Heaven?

(Graham, Angus C., Chuang Tzu – The Inner Chapters, London: George Allen & Unwin, c. 1981, p. 84.)

Mary Poppins really is unmatched as a classical Taoist primer. I’ve discussed only a few key scenes, but the entire movie could serve as an entree into a classical Taoist universe. Disney has released the movie on home video in several formats and editions since 1997. They restored the picture and sound for the 2004 40th Anniversary Edition on DVD.